How to make walking directions better

2017-04-27

I’m working on a navigation app for walking called Whisper Walk. It allows you to explore and walk freely while a voice whispers in your ear roughly which direction to walk. You can read more about it in my previous post.

While working on it, I encountered some problems with finding out exactly which direction a person is walking in. In this post I’ll write about where I started and how I gradually improved the advice Whisper Walk is giving to make it more accurate and timely. Roughly speaking, here are the phases of aha-moments I went through:

- Importance of WiFi for location accuracy

- Limits of naively using delta between current and last position

- Compass as a starting point

- Multiple points and taking accuracy into account

- Statistics to give more timely advice

There are many ways to figure out where a person is or where they are walking, but the most commonly known one is probably the Global Positioning System (GPS). I’ll focus mostly on that, and specifically in the context of what an iPhone gives you. Another tool that is frequently used is the compass. In addition to these two main tools there are a bunch of additional sensors and methods that I’ll talk about briefly at the end.

What’s GPS anyway?

As raw data we have GPS positions coming from the GPS/Location unit in an iPhone. GPS as a system consists of a 20-30 satellites circling the earth. The GPS unit in your smartphone tries to get a clear line-of-sight connection with a few of these. The satellites know where they are, and based on the distance between each satellite and your phone this can be used to triangulate your position.

However, since the satellites are in outer space circling earth, this can take a while. Furthermore, if you are walking in a big city there’s all kind of interference. For example, a tall building will likely block a few GPS signals. And not only that, but the signal might bounce, leading to a longer path and thus a different position.

Importance of WiFi for location accuracy (phase 1)

In addition to all this, this data is often augmented with WiFi signals. This is especially useful in cities, since this is usually where interference is as its highest (tall buildings, semi-indoor areas, etc), and also where the Wifi density is at its highest.

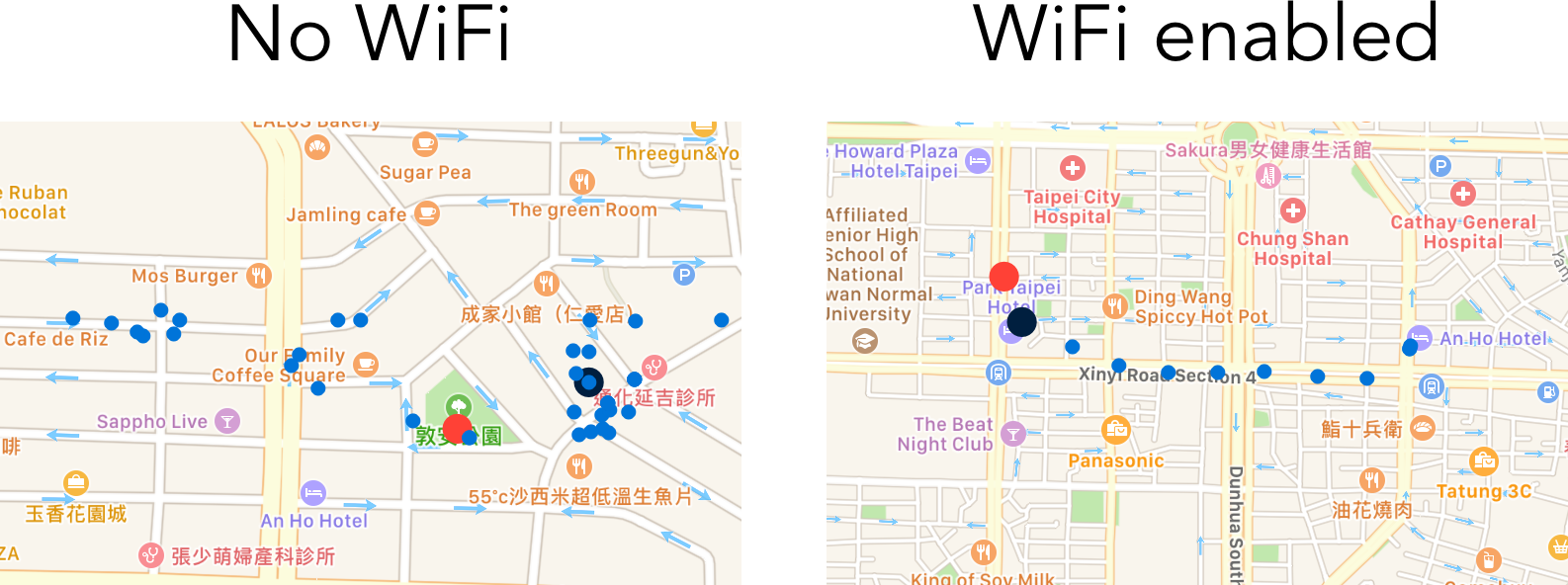

When I started developing Whisper Walk I was only vaguely aware of this. After doing some reading I conducted some tests. The effect is quite staggering, as you can see in the below graph. It’s almost impossible to make out the path walked in the left one, whereas it is very clear in the right one. This “location jumping around” effect makes it difficult to give accurate walking directions.

How does this work? When you have WiFi enabled you can choose a list of networks to connect to. These are all the networks that are close to you, and they have a certain signal strength. Both iPhone/Apple and Android/Google keep a huge crowdsourced table consisting of something like:

- MAC ADDRESS (unique identity of network)

- GPS location (longitude/latitude)

- Timestamp (last detected)

With all this information, your phone can triangulate your position more accurately, and use this in combination with the raw GPS data to give you better directions. Note that this does not require your phone to actually be connected to a WiFi network.

The only tricky part with this is making it work from a UX point of view. As far as I’m aware, there’s no supported way to figure out if WiFi is turned on or not on iPhone. What I’m doing right now is prompting people to make sure their WiFi is turned on, which helps somewhat.

Naively calculating delta between current and last position (phase 2)

Initially I naively took the current position that the location sensor gave me and calculated a delta with the previous location that I received. Even if this was generally accurate when a person is walking and with fairly infrequent updating frequency, this has obvious problems.

Let’s say you are on your way somewhere, but you decide to stop off at a convenience store. If you are standing still, the position updates will keep coming in. There will always be some noise in the reported position. Taking the delta between two such positions will wrongly show some movement in whatever direction. But you aren’t moving, you are standing still!

The solution to this was simple: require a minimum amount of distance between two points before concluding that movement has taken place.

Using compass as a starting point (phase 3)

A compass is a great tool, but there’s a big trade-off: to work, you have to point it somewhere! They are also not always accurate, so they require some manual interpretation. I thus decided to ignore this entirely starting out.

There was a problem with ignoring it completely though. When you walk somewhere, there isn’t any data about where you have been walking, and it’ll generally take a few minutes to get an accurate initial position and tracking.

The solution to this was also fairly straightforward: detect when the user is using the app actively, i.e. it is in the foreground. When they are, use the compass to communicate direction, and then use tracking when the phone is in their pocket. This means a user will get directions advice as soon as they have set their destination and start their journey.

A bug as an opportunity (phase 4)

After a while I noticed there was a bug in my code that led to less frequent position updates than intended. This was partly due to an oversight on my part, and partly due to React Native’s Geolocation module not exposing all the options that were available through Apple’s native API. Long story short, after fixing the bug, I was now getting a lot more data points which meant that I could give direction advice quicker.

This lead to two main changes. The first was to use multiple GPS positions to calculate a segment of movement, and the second was to take the accuracy of each reading into account.

Using multiple GPS positions to calculate a segment of movement

Since I was now getting a lot more frequency updates the distance between current and last position was very small. This meant that there was never any real movement, which was obviously not true. Instead of keeping track of just the last GPS position, I started keeping track of multiple GPS positions. I called this a segment, and I kept track of them until (a) I had detected movement and (b) communicated this in the form of direction advice to a user. To avoid overflowing the user with walking directions, this communication only happens at certainly intervals depending on if the user is going on or off-course, and how close they are to their destination.

Taking accuracy of GPS positions into account

The change also uncovered some limitations to my previously hardcoded minimum distance filter. Because I had a lot more GPS points coming in, they had varying accuracy (oscillating from 10m to 100m to even 1000m). I started recording and paying attention to the reported accuracy of the GPS reading.

The accuracy is a radius of a circle around the position where it is 95% certain the true position actually is. So if the accuracy is 100 meter, then in 19 times out of 20 the user will be maximum 100 meters from the reported location.

The solution I landed upon was to use the minimal distance between the “outer edge” of each position. Let’s say I have a position A that naively is 120m away from position B. The accuracy of position A is 100m whereas the accuracy of position B is 50m. With this information I simply concluded, since 120 - (100+50) is less than 0, that they could be the same area and thus no movement had actually taken place.

This worked OK but it lead to far fewer direction updates. Was there a better way?

Using statistics to give more timely advice (phase 6)

If we have two positions A and B with some naive distance between them, and each with their own reported accuracy, what is the distance between them and how certain can we be about it?

We can state the problem as follows: Given two GPS points that have X and Y meter accuracy 95% of the time, how do we find the minimum distance between them that is accurate Z% of the time?

Assuming normal distributions and independence we have:

X ~ N(mean(x), sd(x)^2)

Y ~ N(mean(y), sd(y)^2)

Z ~ N(mean(x) + mean(y), sd(x)^2 + sd(y)^2)If we know <100m with 95% accuracy that’s the same as 2SD, so 1SD is <50m.

Example 1: A 100m accuracy, B 10m accuracy, both with 95% confidence. Mean is just the naive distance. 1 SD is 50 and 5m respectively, and combined SD is sqrt(50^2 + 5^2)=~50.25. So 2SD or 95% is 101m, i.e. all uncertainty comes from A.

Example 2: A 100m accuracy, B 100m accuracy, both with 95% confidence. Mean is just mean distance. 1 SD is 50 and 50m respectively, and combined SD is sqrt(50^2 + 50^2)=~70.7. So 2SD or 95% is 140m.

To get a different accuracy, we can look it up in a z-table and take the standard deviation times another constant.

Empirically this seems to work, in that direction advice is accurate 95%+ of the time. If we so desired, we could make this arbitrarily more accurate, but there’s a trade-off in accuracy and making the advice timely.

Notice that example 2 gives a minimum required distance of 140m, which is much better than the previously required 200m. This means we can give advice in a more timely manner. which is especially important as you get closer to your destination.

Future work and additional sensors

Before ending this article I want to mention some technologies that can be used to further hone in on your direction.

These include additonal sensors such as gyroscope, speedometer, iBeacon technology, as well as predictive models based on other data, such as maps, heading, speed, etc. For the predictive models a commonly used method is using Kalman filters to deal with multiple sensors and uncertainty. Another is the use of snapping to roads, something that is commonly used for car navigation. One can also get creative with using roads and gyroscope to figure out when a user is likely to have just turned a corner, which has a big impact on direction advice based on how a user is tracking (i.e. how they have moved in the recent past).

As you can tell, there are still a lot of areas of improvement but the direction advice is certainly good enough. When walking somewhere new for longer than 5m I personally prefer using it over looking at a map all the time or using traditional voice nav. But of course I’m biased. Regardless, the primary challenges lie elsewhere for now. Happy walking!

Thanks to Be Birchall and and Dan Luu for comments on this post.